"April 21st 2010 marked the 1110th anniversary of the oldest known written artifact from the Philippines, the Laguna Copperplate Inscription (LCI). 1110 years ago on this date (April 21st of the year 900 in our era), the original legal document was written that forgave a debt held by a person living in the general area now occupied by metropolitan Manila." ~ Christopher MillerLearn more about the Laguna Copperplate Inscription [click here]

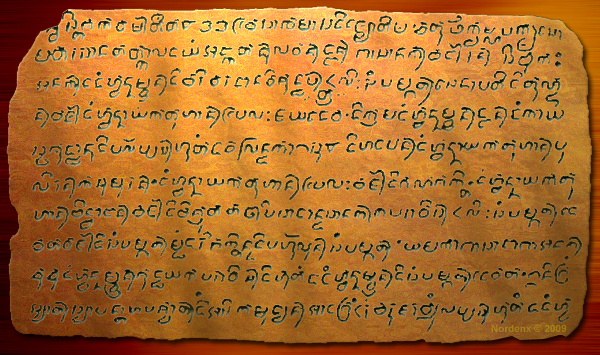

Did you know that the LCI contains enough glyphs that fills an almost complete chart for old Javanese/Kavi? The image below contains all the deciphered glyphs found in the LCI:

Though a lot of details & characters are still missing, one only needs to take a look at the parent and related writing systems like Sanskrit and Old Javanese to figure out how rich and complex our ancestor's (proto-baybayin) writing system was prior to the emergence of the more simplistic classical baybayin script.

A couple of features that stand out from the LCI is that the Javanese Srivijaya inhabitants of our pre-colonial archipelago used a virama (vowel cancellation mark), the same function as the cross kudlit except that the LCI virama is only used for a final vowel-less trailing consonant. As for a vowel-less leading consonants, the glyphs form syllables by consonant conjuncts or stacked where the initial glyphs' vowel is dropped; quite similar to other Indic/Brahmic scripts of Hindu inhabitants that co-existed with the Javanese society in the islands at the same era.

We can find glyphs for visarga and anusvāra in the LCI.

An anusvāra is a diacritic used to mark a nasalization used in a number of Indic languages. This eliminated the use of a virama on a nga glyph for that final ng sound.

A visarga is a diacritic used to mark a voiceless breath used in a number of Indic languages. Losing this diacritic may explain the lost 'h' on certain words in modern Tagalog orthography.

Instead of adding a diacritic on the final vowel of a word with a final stress, note that LCI uses a diacritic for a long "a" or ā on the leading syllable's glyph.

Along with the long ā, the LCI shows us that the ancient islanders have all of the markers needed for five vowel sounds plus another for "ai" and a simple and modern-like "period" punctuation mark.

Note the characters for "ra", "ja", and "sha"; nevermind the "ca" and "ña" - wonder why these glyphs from Kawi did not carry through to baybayin? Sanskrit (parent script for both baybayin and kawi) also has these phonemes covered. One has to ponder when, how, and why our spoken language changed so much that the letters for these sounds are dropped from our spoken & written language. What happened between the time of the LCI until the re-introduction of letters and matching phonemes after the arrival of westerners? A proto-baybayin script may have been developed by the people for their own social class' usage by emulating features of Old Kawi and Sanskrit (that were propriety to the ruling & religious class). If this is the case, then the disparity and disconnect between social classes already existed in our ancient society even before western corruption entered the scene.

The few examples of alternate or modified sub-scripted and super-scripted character glyphs and those that form character conjuncts are surprisingly varied and complex (like those of "ra" and "ya"), I wouldn't be surprised that there are more letter combinations that are possible but not recorded in the LCI; other artifacts with Kawi from outside of the Philippines could fill in those gaps. For more examples and info, see: Aksara Kawi or Omniglot.

.

.*edit - Additional Info:

Note that the LCI glyphs are Old Javanese Kawi Script with just a few peculiar character variations. This is probably due to the way the characters on the Laguna plate seemed to have been hammered into cold copper instead of the characters being impressed into heated copper which was the norm in Java at the time.

Also, the language used in the Laguna Copperplate Inscription is a variety of Old Malay containing numerous loanwords from Sanskrit and a few non-Malay vocabulary elements from Old Javanese and Old Tagalog (Austronesian).

Other artifacts of interest:

* Kedukan Bukit Inscription

* Tanjong Tanah Code of Law

Resources:

Many thanks to Antoon Postma, Dr. Johann de Casparis, Hector Santos, Paul Morrow for sharing their translations and research about the LCI.

Thanks to linguist and SEA script expert Christopher Miller (Kiwehtin) for providing additional info (please read comments) and visit Tyro Blog.

8 comments:

You raise several interesting issues here, so I'm going to reply in three responses to keep each under the character limit. Here's the first part:

You should try to get hold of Johannes de Casparis' _Indonesian Palaeography_. It's an excellent book that deals with mostly stone and metal inscriptions in the archipelago up to 1500. It has several illustrations (with transliterations) of other texts in early standard Kawi script, of which the LCI is just one example. The main peculiarity of the LCI characters is that the ‹a› and ‹u› don't have the '3' shapes you normally find elsewhere; otherwise it's pretty close to what you see in the other standard Kawi samples. You're sure to find other examples of conjuncts in those.

Examples of a wide variety of Kawi and other Indic scripts are reproduced in Holle's famous _Tabel van Oud- en Nieuw-Indische Alphabetten_ which can be downloaded online from Google Books. (The title is misspelled there as "Table".)

Another interesting place to look is at the Tanjung Tanah manuscript which is from the late 14th century, therefore 400 years or so after the LCI. It's an example of the late Kawi script as used in Sumatra in Adityawarman's kingdom. Although Uli Kozok suspects this might be a development from Kawi indigenous to Sumatra, it is so similar to late Kawi/old Javanese scripts attested in Holle's tables that it is quite likely it was just imported from Java when Adityawarman moved from there to conquer himself a kingdom in Sumatra. You can find it, with photographs, here:

http://ulikozok.com/TT-pub.html

Kozok gives a transliteration and photos of each page in his various papers and actually has a separate Tanjung Tanah page at his university of Hawai'i site.

As for Antoon Postma's original paper on the LCI, which transliterates and translates it with discussion of the sociological and cultural environment in which it was written, it was published in the Philippine Journal of Linguistics, which is unfortunately extremely hard to get hold of: my attempts to contact the Journal for information have gone without response. However, I found a PDF version online which I would be glad to share with you if you like.

Thank you for your insight. I too have been trying to get a hold of Antoon Postma's original paper on the LCI and most of his work on the Mangyan. I have been unsuccessful as well. I would be very grateful if you could share a copy of the PDF you found.

Interesting, I'd never seen anyone pull the LCI kawi apart and "pick out" its specific glyphs, diacritics, and conjuncts before.

Speaking of the LCI, I've done my own transcription in a constructed Indic script of my own Another transcription of the LCI

It's not exactly an exact transcription (as it ignores vowel length), but it was more of a "thought experiment" to see what the LCI would look like in another Indic styled script.

Here's a link for the Postma 1992 article on the LCI, and while I'm at it, a little file I put together a while ago to show that the rhinoceros horn seal from Butuan is all in Kawi, and not in Kawi mysteriously missing its vowel markings and upside-down Baybayin also mysteriously missing *its* vowel markings, as many believe:

http://files.me.com/christophermiller/o8ozse

http://files.me.com/christophermiller/y4ome9

I put together the various illustrations from the samples in Holle that had a subscript ‹b›, modern Balinese (which is nearly identical to the oldest modern Javanese style found in the early 1600s) plus Latin and Baybayin for comparison.

It's also very much worthwhile getting hold of _Das Buch der Schrift_ by Faulmann (Google Books). The book has detailed reproductions of Indic script samples starting at his page 115. Page 122 has some very interesting samples of Gupta dynasty scripts from the first few centuries of our era. These are the ancestors of all North Indian scripts and it is very informative to see how close the letter shapes are overall to those of Kawi, which dates to approximately the same era. On page 142 and the following pages, he illustrates what he calls "Pali" script, or rather as he says, a group of scripts used to write the Buddhist liturgical language Pali. You can see the close relationship between these scripts and Kawi, and a few pages later, how Burmese script is basically the same but all written in circles and semicircles. (Although it's usually said that Kawi descends from Pallava script, de Casparis himself only says that the Pallava inscriptions precede Kawi in date, and cautions against concluding that means Kawi derives from Pallava especially since Pallava has the characteristics of a script especially designed for monumental inscriptions unlike Kawi, a practical everyday script designed to be written on palm leaf.

In response to your question about the presence of ‹r›, ‹j›, ‹c› and ‹sh› letters in the LCi and their absence in baybayin, the answer has two parts.

The first part is the fact that the LCI was beyond any doubt written not in any form of Tagalog but in Old Malay, with borrowings from Sanskrit and several words that were likely borrowed from Javanese or possibly (though less likely given their form) from Tagalog. Malay had all these sounds, and therefore naturally used the appropriate letters to write them with (though ‹sh› only occurred in Sanskrit loans).

The second part of the answer is that Tagalog itself, as a Philippine language, had none of these sounds. Where you have /r/, /j/, /c/ in Malay, Tagalog (and other Philippine languages more or less generally) will have /l/ (or /g/), /d/ and /t/ instead. The Philippine /l/ and /g/ come from Proto-Austronesian sounds reconstructed as */r/ and */R/: the first was likely a simple tapped /r/ and the second a trilled /rr/. In Malay and most of the western Indonesian languages, these both merged to a single /r/ phoneme, whereas in Philippine languages the /R/ moved back in the mouth (like trilled /rr/ in French, Puertorriqueño Spanish or Portuguese), ending up pronounced as a sound similar to (but not exactly the same as) English /g/.

This is why words like magaral in Tagalog and belajar in Malay are directly related: they both descend from a Proto-Austronesian word reconstructed as *maRazar. This became something like *barajar in proto-Malay, which then changed into Modern Malay belajar; in the Philippines the /z/ and /r/ regularly changed to /d/ and /l/, giving a likely proto-Philippine *magadal, which came to be pronounced as magaral in modern Tagalog. You can find more details about how the sound systems of the Philippine languages likely evolved here:

http://www.persee.fr/web/revues/home/prescript/article/arch_0044-8613_1975_num_9_1_1214

Other examples: Indonesian/Malay 'jalan' (road) is directly related to Tagalog 'daan', and the word 'surat' (write, originally meaning scratch or cut) apparently originally relates to Tagalog 'sugat' (wound or cut); 'sulat' appears to be a later borrowing, probably from Malay or perhaps Javanese, where the /r/was changed to /l/ because Tagalog – like most Philippine languages – had no /r/ phoneme. (I forget where exactly this comes from among the many linguistic papers on Philippine and Austronesian languages I have on my computer; in any case, Llamzon in his article above seemed not to be aware of this particular etymological link.) And finally, the Sanskrit root 'cinta' (want, love) was borrowed into Malay as 'cinta', but in the Philippines became 'sinta' because Philippine languages had no /c/ sound.

The changes from proto-Austronesian to proto-Philippine and proto-Malayic likely took place over two millennia ago at least, a time period way before any writing system was introduced to any of the languages in the archipelago, indeed probably before the original Brahmi script sprung up in India a mere 3 to 5 centuries BCE.

As for the absence of the various extra subordinate marks (virama, visarga etc.), this is explained by the hypothesis that Baybayin was adopted from earlier users in Sulawesi: Makassarese (or perhaps Buginese) traders would have adopted the newly developed "Malay" script from south Sumatra somewhere around the early 1400s but discarded all the extra marks used in the Sumatran scripts since syllables in Bugis and Makassarese either end in a vowel, a vowel plus a glottal stop (which often surfaces as a doubled consonant inside a word) or a vowel plus /ng/ (which surfaces as m or n inside a word, depending on the following consonant). Since the number of possible readings is in practice easy to tell apart for a fluent speaker of Bugis or Makassarese, they didn't feel a need to use any marks to write their languages beyond the subordinate vowel marks for /i/, /u/, /e/ and /o/ (plus neutral /e/ in Bugis).

When people in the Philippines adopted an old version of the Sulawesi script (that has since simplified to its current minimalist form in Sulawesi), the only vowels they needed were the ‹i› and ‹u› marks: apart from /a/, those were the only other phonemic vowels in Philippine languages. Although they likely would have gladly adopted the virama if there were one (the Sumatrans were using it with abandon to write their own languages which were also rich in syllable-final consonants, as well as visarga, anusvara, repha and later on even a second anusvara-like -n borrowed from Arabic), the Sulawesi script had no virama available, so the writers in the Philippines just had to make do with the resulting semi-telegraphic spelling system.

Just a little correction: I'm not actually the author of the Tyro blog. I have made various comments there and shared information from my own work on baybayin that I have been doing since last October, as I have also on the Alibata Yahoo! group and the Facebook Alibata page. So although you can see my input there, I'm not actually the writer of the blog itself.

Ah yes, Tyro is where I remember the name "Kiwehtin" from. Apologies. I was too quick to post witout double checking. ;) Thanks for the correction.

Post a Comment